| Scientific Name | Ocotea bullata (Burch.) Baill. | Higher Classification | Dicotyledons | Family | LAURACEAE | Common Names | African Acorn (e), African Oak (e), Bean Trefoil (e), Black Laurel (e), Black Stinkwood (e), Cannibal Stinkwood (e), Cape Laurel (e), Cape Olive (e), Cape Stinkwood (e), Cape Walnut (e), Kaapse Lourier (a), Kaapse Stinkhout (a), Laurel Wood (e), Laurelhout (a), Stinkhout (a), Stinkwood (e), Swartstinkhout (a), Swart-stinkhout (a), Swartstinkhoutboom (a), Umhlungulu (x), Umnimbithi (x), Umnukane (z), Umnukane (x), Umnukani (z), Umnukani (x), Unukane (z), Witstinkhout (a) |

National Status | Status and Criteria | Endangered A2bd | Assessment Date | 2008/01/14 | Assessor(s) | V.L. Williams, D. Raimondo, N.R. Crouch, A.B. Cunningham, C.R. Scott-Shaw, M. Lötter, A.M. Ngwenya & A.P. Dold | Justification | The species was heavily exploited for the timber industry in the past, and more recently for bark for the traditional medicine trade. Despite its wide, but disjunct, distribution, subpopulations in at least 53% of its range have been heavily exploited, rendering them extinct, near-extinct, rare, scarce or fragmented. We estimate a minimum of 50% population reduction in the last 240 years (generation length 80 years). |

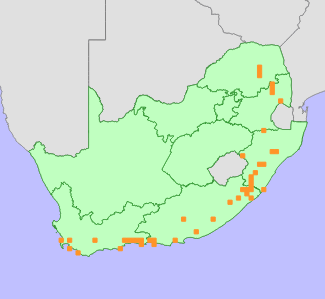

Distribution | Endemism | South African endemic | Provincial distribution | Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal, Limpopo, Mpumalanga, Western Cape | Range | It is widespread in South Africa from the Cape Peninsula to the Wolkberg Mountains in Limpopo. |

Habitat and Ecology | Major system | Terrestrial | Major habitats | Northern Coastal Forest, Southern Coastal Forest, Scarp Forest, Northern Mistbelt Forest, Southern Mistbelt Forest, Northern Afrotemperate Forest, Southern Afrotemperate Forest | Description | Plants grow in high, cool, evergreen Afromontane forests. |

Threats | | The main threats to Ocotea bullata are timber logging in the past, and bark harvesting in the recent past, present and future.

Commercial timber exploitation: Since the mid-1700s Ocotea bullata has been heavily exploited for its very valuable timber in the southern Cape, especially in the forests between George and Plettenberg Bay (e.g. Sim 1906, Phillips 1931, King 1939 and 1941). It was regarded as one of the top 3 valuable timber species throughout the country. Harvesting in George commenced around 1772, but timber was extracted from the Cape Peninsula in unknown large quantities before that. In 167 years from 1772-1938, King (1941) estimated that 4.5 million cubic feet (120 347 cubic meters) of Ocotea was felled in forests between George and Plettenberg Bay. This is an annual average of 721 cubic meters. Sim (1906) estimated that the average Ocotea stem yielded 0.4 cubic meters of timber, hence an estimate of the total number of Ocotea trees felled in the region over 167 years is 300 868 - an average of 1802 trees per annum. Many State forests in the region were reduced to a state of complete exhaustion (King 1939). In some periods the mean annual volume of Ocotea harvested was much higher (e.g. from 1889-1905 the average annual volume was 1255 cubic meter or 3138 trees). (Sim also recorded 38 759 Ocotea trees actually felled from 1889-1900). However, in the period 1931-1938 the volumes drastically declined to 413 cubic meters per annum (1032 trees/a). Current trends indicate a much reduced volume currently being harvested from southern Cape forests. Lawes et al. (2004, pg 247) list the amount of Ocotea sold at auctions from 1996-2001 to be 925 cubic meters (or 154 cubic meters per annum). In 1900, the number of 'mature'/marketable trees in southern Cape forests with a diameter at breast height (dbh) greater than 46 cm was 13%. By 1930, it was 1.7% (King 1939).

Timber harvesting in the Eastern Cape in the region of the Amatole forests must have begun shortly before 1847 (King 1941). The species must have been rare within the region because figures for timber volumes are usually absent (e.g. Sim 1906) or included within the 5% cited for 'other species' (King 1941). Timber extraction within the former Transkei began before 1888. Selective "culling" of yellowwood and stinkwood appears to have been the norm until a quota system was introduced in 1936. In 1904, a saw mill was established near the Tonti forest - an area once rich in Ocotea and regarded as the most valuable forests in the Cape Colony. In 1924, the unexploited part of the forest contained 74 cubic meters per acre of merchantable timber - 15% of which was Ocotea. Few figures exist, however, for the Ocotea timber volumes extracted from the region.

In KwaZulu-Natal, commercial timber exploitation commenced in the mid-1800s (McCracken 1986). It was estimated that 400 000 cubic meters of indigenous timber was extracted from the Karkloof forest in the 1860s [over-exploitation began there around 1845 (Rycroft 1944)]. There were also ±18 saw mills operating in the Natal Midlands by the 1870s. Ocotea was one of the preferred timber species. In a report on forests in the Natal Colony (Bulwar 1878), Ocotea was a principle timber tree in the Karkloof forest (ranked 4th), but was fast disappearing. By 1878, comparatively little remained except for inferior and damaged trees. The larger trees were cut for commercial purposes and saplings were frequently "cut by natives" for fences, kraals, huts etc. In a report of the Natal Forests by Fourcade (1889), Ocotea was present in several Drakensberg upland and Midlands forests that had been extensively logged and were now very damaged. It was never the principle species in the forest, but its presence/absence was usually noted because of its high value. By 1889, Ocotea in the Hlabeni, Ingeli and Zwaartkop forests was recorded as having been cut out (especially in Zwaartkop, near Pietermaritzburg). Over-exploitation of the KwaZulu-Natal midland forests has been a major factor in stinkwood population reduction (Morty and Johnson 1987). Few quantitative data exist concerning the scale of cutting in KwaZulu-Natal, but stinkwood stumps are common in forests where living specimens are now rare. Furthermore, most good Ocotea specimens are to be found far from roads or on steep slopes.

In the eastern Transvaal forests (now part of Mpumalanga and Limpopo), Ocotea was cut in large quantities after the discovery of gold in the Witwatersrand c.1886 so that today few fine quality specimens remain (Palmer and Pitman 1972).

Bark harvesting: Ocotea bark has probably always been harvested for medicine, but due to massive declines augmented by timber harvesting and the commercialisation of the traditional medicine trade, bark harvesting is probably the species current biggest threat causing significant declines. Trees, especially in KwaZulu-Natal and part of the Eastern Cape, are already rare due to extensive timber harvesting in the 1800s, and it is the combined impact with bark harvesting that is killing off the few remaining individuals. Over-exploitation of Ocotea in KwaZulu-Natal has resulted in a shift to exploiting it in the Eastern Cape (Cunningham 1988). The Karkloof Forests (as seen below) appear to be especially vulnerable in KwaZulu-Natal.

One of the earliest records of Ocotea bark being harvested for muthi is from the Karkloof Forest (Rycroft 1944). However, unlike today, it was customary not to remove more than one piece of bark from a tree or to "tamper with" malformed trees. This practice, however, still made trees susceptible to fungal decay and mortality. The second record of bark harvesting for muthi is also from the Karkloof (Taylor 1961). In 1958, large-scale exploitation of Ocotea was recognised as a lucrative business by a European landowner and workers were instructed to strip trees (for a small commission) in the Ehlatini region and sell the bark to Durban medicine men. Unfortunately, the workers also trespassed on adjacent forest properties and damaged large numbers of trees. On one farm, every stinkwood tree with a dbh of 10-50 cm had been ring-barked, sometimes as high as ?6 m. Bark removal was also speculated to account for the complete absence of Ocotea in the Nxamalala forests (Taylor 1963). In Weza, Dally (1984) reported that there had been an increase in Ocotea bark harvesting activities in the past 12 months and that 48 trees with various stages of bark damaged were counted. Oatley (1979) estimated that in private forests in Karkloof, only 1% of trees were undamaged and 33% were dead. Rough counts of trees in privately-owned forests in Dargle, Karkloof, Boston, Impendle, Creighton and Harding areas of KwaZulu-Natal found that 95% of all Ocotea trees had been damaged, and of these about 40% had been completely ring-barked (Cooper 1979). Morty and Johnson (1987) reported that 36 out of 40 forests they surveyed had evidence of bark stripping - mostly over 50% of the stem. Cunningham (1988) conducted a survey of 3 Ocotea sites (Karkloof, eMalowe, Ngunjini) and found at least 51% of trees had had more than 50% of the bark removed. In 1988, the estimated annual demand by 54 herb-traders in the Durban markets was ±234 bags (50kg-size), which is equivalent to ± 468 trees (assuming 1 bag may contain bark from 2 trees 40-40cm dbh). The scarcity of the bark was consistently ranked 1st by most herbalists and traders. Mander (1998) estimated there was a 25% increase in travel time from 1988 to 1998 to reach Ocotea localities. Major harvesting locations cited were Ixopo, Umzimkulu and Lusikisiki. In terms of the Witwatersrand trade, 68% of muthi shops sold it in 1994 (ranked 7th in prevalence) and it ranked 3rd in scarcity citations Williams (2000). In the Faraday market (Williams 2003), the species was scarce and only 9% of traders sold it. The bark volume present in the market at the time of the survey was 1.7 bags (50kg-sized). However, there is a possibility that this species is being substituted with Cryptocarya spp. in the markets due to its scarcity. Cited sources of bark included Howick, Greytown mountains and Nkandla. Geldenhuys (2004) recorded 359 Ocotea stems in 37 transects through forests in the Umzimkulu district. 206 stems (57.4%) had been stripped for bark - some up to 12m. Many larger trees had been felled to reach bark higher up the stem. On average, more than 30% of bark on a stem had been removed.

Root rot pathogen: Since 1970, the number of dying Ocotea trees seems to have increased in the southern Cape forests (Lubbe 1989). The cause of the decline was linked to habitat disturbance, past/present logging from 1868 and selective harvesting activities. This caused changes in water drainage around the trees and a tendency for water-logging. Trees became more susceptible to the root rot pathogen Phytophtora cinnamomi, especially trees in clumps of ?2 individuals. The pathogen was discovered in 17 localities in 4 forests and was associated with 88% of the dying or potentially dying trees. A survey in 3 southern Cape forests by Lubbe and Mostert (1991) also noted a significant rate of Ocotea decline and die-back in 1986. This die-back was associated with the occurrence of P. cinnamomi and coincided with stress factors such as water-logging associated with site disturbance.

Seed predation: Nearly all the flowers are attacked by a fungus and are infertile (Palmer and Pitman 1972). The species fruits abundantly at times, but the fruit seldom ripens on the tree because it is attacked by boring insects and eaten by some forest birds and fruit bats. Of the seed which falls to the ground, less than 1% is viable due to attacks from other insects and consumption by fruit-eating mammals (Mitchell 1961)

Lack of fruit vectors: (see fragmentation notes for more detail). Refers to the changing diet of the rameron pigeon from eating Ocotea fruits to that of the exotic Solanum mauritianum (Oatley 1984). The ability of the species to disperse through seeds is thus further reduced

Browsers: Ocotea has the ability to regenerate through coppicing. Bushbuck tend to browse very heavily on coppice shoots and account for high mortality (Scott-Shaw 1999).

Additional comments from C.R. Scott-Shaw (pers. comm., February 2008):

a) the critical sensitivity of Black stinkwood to bark removal is very important in comparison to all other canopy species in the mistbelt forest. Trees die very easily. They do usually coppice, but now the saplings have to contend with the browse obsessions of bushbuck - a well known favourite of theirs. Then, it has to try and compete for resources such as sunlight.

b) Some of the staff at KZN/Ezemvelo-Wildlife, including C.R. Scott-Shaw, have revisited many of the forests surveyed by Morty and Johnson. The species has subsequently become extinct in the following forests: Pongola Bush, Nkandla, Rokeby Park, Marutswa, Ingelabantwana, Cathedral Peak. Some areas like Mpendle have a few small groups of small trees from coppice growth.

c) Since 1974, Ocotea has been the only forest tree listed for protection in our ordinance. Now 34 years later, it still tops the short list of trees of our proposed new schedules.

Additional comments from an email from A.P. Dold (pers. comm., February 2008):

"I spoke to a colleague at DWAF in King William's Town, and she tells me that they have records of only 6 trees in the Amathole Forests and the localities are strictly confidential. I have checked several checklists for the Amathole's and Alexandria forest (Pete Phillipson did both) and haven't found additional records.". |

Population | Population trend | Decreasing |

Conservation | | It is conserved in Pongola Bush, Impendle and Karkloof Nature Reserves. |

Assessment History |

Taxon assessed |

Status and Criteria |

Citation/Red List version | | Ocotea bullata (Burch.) Baill. | EN A2bd | Raimondo et al. (2009) | | Ocotea bullata (Burch.) Baill. | Lower Risk - Conservation Dependent | Scott-Shaw (1999) | | Ocotea bullata (Burch.) Baill. | Vulnerable | Hilton-Taylor (1996) | |

Bibliography | Anonymous. 1993. Ocotea bullata. The Indigenous Plant Use Newsletter 1:8.

Boon, R. 2010. Pooley's Trees of eastern South Africa. Flora and Fauna Publications Trust, Durban.

Bulwar, H.E. 1880. Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into and report upon the extent and condition of forest lands in the colony. Natal Blue Book. Watson, Government Printer, Pietermaritzburg.

Coates Palgrave, K. 1977. Trees of Southern Africa. Struik Publishers, Cape Town.

Cooper, K. 1979. A muti man stinkwood racket. African Wildlife 33:8.

Cunningham, A.B. 1988. An investigation of the herbal medicine trade in Natal/KwaZulu. Investigational Report No. 29. Institute of Natural Resources, Pietermaritzburg.

Da Silva, M.C., Izidine, S. and Amude, A.B. 2004. A preliminary checklist of the vascular plants of Mozambique. Southern African Botanical Diversity Network Report 30. SABONET, Pretoria.

Dally, K. 1984. Illegal debarking of stinkwood. Forestry News 4:23.

Diniz, M.A. 1997. Lauraceae. In: G.V. Pope (ed). Flora Zambesiaca 9 (Part 2):45-59. Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew.

Fourcade, H.G. 1889. Report on the Natal Forests. Natal Blue Book. Government Printer, Pietermaritzburg.

Geldenhuys, C.J. 2004. Meeting the demand for Ocotea bullata bark. Implications for the conservation of high-value and medicinal tree species. In: M.J. Lawes, H.A.C. Eeley, C.M. Shackleton and B.G.S. Geach (eds.), Indigenous Forests and Woodlands in South Africa: Policy, People and Practice (pp. 517-550), University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg.

Goldblatt, P. and Manning, J.C. 2000. Cape Plants: A conspectus of the Cape Flora of South Africa. Strelitzia 9. National Botanical Institute, Cape Town.

Hilton-Taylor, C. 1996. Red data list of southern African plants. Strelitzia 4. South African National Botanical Institute, Pretoria.

King, N.L. 1939. The Knysna forests and the woodcutter problem. Journal of the South African Forestry Association 3:6-15.

King, N.L. 1941. The exploitation of the indigenous forests of South Africa. Journal of the South African Forestry Association 6:25-48.

Lawes, M.J., Midgley, J.J. and Chapman, C.A. 2004. South Africa's forests: the ecology and sustainable use of indigenous timber resources. In: M.J. Lawes, H.A.C. Eeley, C.M. Shackleton and B.G.S. Geach (eds.), Indigenous Forests and Woodlands in South Africa: Policy, People and Practice (pp. 31-75), University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg.

Lawes, M.J., Obiri, J.A.F. and Eeley, H.A.C. 2004. The uses and value of indigenous forest resources in South Africa. In: M.J. Lawes, H.A.C. Eeley, C.M. Shackleton and B.G.S. Geach (eds.), Indigenous Forests and Woodlands in South Africa: Policy, People and Practice (pp. 227-273), University of Natal Press, Pietermaritzburg.

Lubbe, W.A. 1989. Response of stinkwood to stress. Forestry News 9:16-19.

Lubbe, W.A. and Geldenhuys, C.J. 1990. Decline and mortality of Ocotea bullata trees in the southern Cape forests. South African Forestry Journal 154:7-14.

Lubbe, W.A. and Mostert, G.P. 1991. Rate of Ocotea bullata decline in association with Phytophtora cinnamomi at three study sites in the southern Cape indigenous forests. South African Forestry Journal 159:17-24.

Mander, M. 1998. Marketing of indigenous medicinal plants in South Africa: a case study in KwaZulu-Natal. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

McCracken, D.P. 1986. The indigenous forests of colonial Natal and Zululand. Natalia 16:19-38.

Mitchell, A.D. 1961. Random notes on stinkwood (Ocotea bullata). The South African Forestry Association 36:11-13.

Mortey, K.E. and Johnson, D.N. 1987. The status and conservation of the black stinkwood in Natal. Lammergeyer 38:60-67.

Oatley, T.B. 1984. In: Exploitation of a new niche by the Rameron Pigeon Columba arquatrix in Natal (pp. 323-330). Paper presented at the Proceedings of the Fifth Pan-African Ornithological Congress, Johannesburg, Southern African Ornithological Society.

Palmer, E. and Pitman, N. 1972. Trees of southern Africa covering all known indigenous species in the Republic of South Africa, South-West Africa, Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. Volume 2. A.A.Balkema, Cape Town.

Phillips, J.F.V. 1931. Forest-succession and ecology in the Knysna region. Department of Agriculture. Government Printer, Pretoria.

Pooley, E. 1998. The complete field guide to trees of Natal, Zululand and Transkei. Natal Flora Publications Trust, Durban.

Raimondo, D., von Staden, L., Foden, W., Victor, J.E., Helme, N.A., Turner, R.C., Kamundi, D.A. and Manyama, P.A. 2009. Red List of South African Plants. Strelitzia 25. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

Rycroft, H.B. 1944. The Karkloof Forest, Natal. Journal of the South African Forestry Association 11:13-25.

Schmidt, E., Lotter, M. and McCleland, W. 2002. Trees and shrubs of Mpumalanga and Kruger National Park. Jacana, Johannesburg.

Scott-Shaw, C.R. 1999. Rare and threatened plants of KwaZulu-Natal and neighbouring regions. KwaZulu-Natal Nature Conservation Service, Pietermaritzburg.

Sim, T.R. 1906. The Forests and Flora of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope. Government of the Cape of Good Hope, Pietermaritzburg.

Taylor, H.C. 1961. The Karkloof forest: a plea for its protection. Forestry in South Africa 1:123-134.

Taylor, H.C. 1963. A report on the Nxamalala Forest. Forestry in South Africa 2:29-43.

Williams, V.L. 2003. Hawkers of health: an investigation of the Faraday Street traditional medicine market in Johannesburg. Report to Gauteng Directorate for Nature Conservation, DACEL.

Williams, V.L., Balkwill, K. and Witkowski, E.T.F. 2000. Unravelling the commercial market for medicinal plants and plant parts on the Witwatersrand, South Africa. Economic Botany 54(3):310-327.

|

Citation | | Williams, V.L., Raimondo, D., Crouch, N.R., Cunningham, A.B., Scott-Shaw, C.R., Lötter, M., Ngwenya, A.M. & Dold, A.P. 2008. Ocotea bullata (Burch.) Baill. National Assessment: Red List of South African Plants version 2024.1. Accessed on 2026/01/22 |

Comment on this assessment Comment on this assessment

|

© D. Turner  © D. Turner  © S. Falanga  © S. Falanga  © M. Lötter  © M. Lötter  © M. Lötter  © M. Lötter  © G. Nichols

Search for images of Ocotea bullata on iNaturalist

|

Comment on this assessment

Comment on this assessment