| Scientific Name | Cryptocarya myrtifolia Stapf | Higher Classification | Dicotyledons | Family | LAURACEAE | Synonyms | Cryptocarya vacciniifolia Stapf | Common Names | Camphor Tree (e), Igqebe (z), Isithungwa (x), Kanferboom (a), Mirtekweper (a), Mirte-kweper (a), Myrtle Quince (e), Myrtle Wild-quince (e), Umgqebe (x), Umkhondweni (z), Umncatyana (x), Umngqabe (z), Umqqebe (x), Umthungwa (x), Wild Camphor (e), Wild Camphor Tree (e), Wilde-kanferboom (a) |

National Status | Status and Criteria | Vulnerable A2cd | Assessment Date | 2008/01/15 | Assessor(s) | V.L. Williams, D. Raimondo, A.P. Dold, N.R. Crouch, A.B. Cunningham, C.R. Scott-Shaw, M. Lötter & A.M. Ngwenya | Justification | There has been an estimated population reduction of over 30% in the last three generations (150 years) due to bark harvesting, deforestation and habitat loss for urban expansion in the greater Durban area. It is therefore listed as Vulnerable under criterion A. |

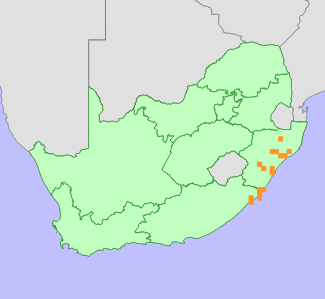

Distribution | Endemism | South African endemic | Provincial distribution | Eastern Cape, KwaZulu-Natal | Range | This species is endemic to the KwaZulu-Natal and Eastern Cape provinces of South Africa. |

Habitat and Ecology | Major system | Terrestrial | Major habitats | Northern Coastal Forest, Scarp Forest, Southern Mistbelt Forest | Description | Plants grow in evergreen, mistbelt and scarp forests, on steep slopes and valley bottoms, close to waterfalls and streams. |

Threats | | The bark of this species is used for traditional medicine and is sold in the Durban and Johannesburg medicinal plant markets. The species is often used interchangeably with Cryptocarya latifolia and C. woodii. Cunningham (1988) classed as it 'declining' in KwaZulu-Natal because wild populations were being destroyed by harvesters. Cunningham (1988) also estimated that 228 bags (50kg-size) of Cryptocarya spp. (C. myrtifolia and C. latifolia) were being sold annually by 54 herb-traders in the Durban region. Mander (1998) reported that it is among the medicinal species most frequently demanded by consumers in KwaZulu-Natal. Williams (2007) recorded that 62% of Witwatersrand muthi shops in 1994 and 2% of the Faraday market street traders in 2001 sold Cryptocarya spp. Destructive bark harvesting has been witnessed, and it has been heavily exploited for bark products. The bark is not very visible in the muthi markets and hence small volumes are present - probably due to its scarcity (M. Ngwenya, pers. comm., 2008). Scott-Shaw (1999) classified it as "Lower risk - least concern".

Debarked trees do not recover easily, and coppice production from bark wounds and basal regions is poor (Geldenhuys 2001, cited in Grace et al. 2003). Geldenhuys recommends that bark harvesting should be limited to narrow vertical strips to facilitate regeneration (cited in Grace et al. 2003).

Because Cryptocarya spp. contains various aromatic compounds, it is has become a recent substitute for the now-scarce Ocotea bullata. Hence, the current exploitation of C. myrtifolia is partly a consequence of the past exploitation of O. bullata (N.R. Crouch, pers. comm., 2008).

It was estimated by participants at the Medicinal Plant Red List Workshop (14-15/01/2008, SANBI, Durban) that there has been decline of over 30% in the population in the last 150 years (generation length = 50 years). Threats to the species that have resulted in this decline include bark harvesting for muthi and habitat loss. A large proportion of the scarp forest has been lost due to excessive resource use (R. Scott-Shaw, pers. comm., 2008). There has been a loss of habitat in the greater Durban areas, and deforestation and alien invasive plant species are also a problem. |

Population | Population trend | Decreasing |

Assessment History |

Taxon assessed |

Status and Criteria |

Citation/Red List version | | Cryptocarya myrtifolia Stapf | VU A2cd | Raimondo et al. (2009) | | Cryptocarya myrtifolia Stapf | Lower Risk - Least Concern | Scott-Shaw (1999) | |

Bibliography | Boon, R. 2010. Pooley's Trees of eastern South Africa. Flora and Fauna Publications Trust, Durban.

Cunningham, A.B. 1988. An investigation of the herbal medicine trade in Natal/KwaZulu. Investigational Report No. 29. Institute of Natural Resources, Pietermaritzburg.

Grace, O.M., Prendergast, H.D.V., Jager, A.K. and Van Staden, J. 2003. Bark medicines used in traditional healthcare in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa: an inventory. South African Journal of Botany 69(3):301-363.

Mander, M. 1998. Marketing of indigenous medicinal plants in South Africa: a case study in KwaZulu-Natal. Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Rome.

Palmer, E. and Pitman, N. 1972. Trees of southern Africa covering all known indigenous species in the Republic of South Africa, South-West Africa, Botswana, Lesotho and Swaziland. Volume 2. A.A.Balkema, Cape Town.

Pooley, E. 1998. The complete field guide to trees of Natal, Zululand and Transkei. Natal Flora Publications Trust, Durban.

Raimondo, D., von Staden, L., Foden, W., Victor, J.E., Helme, N.A., Turner, R.C., Kamundi, D.A. and Manyama, P.A. 2009. Red List of South African Plants. Strelitzia 25. South African National Biodiversity Institute, Pretoria.

Scott-Shaw, C.R. 1999. Rare and threatened plants of KwaZulu-Natal and neighbouring regions. KwaZulu-Natal Nature Conservation Service, Pietermaritzburg.

Williams, V.L. 2007. The design of a risk assessment model to determine the impact of the herbal medicine trade on the Witwatersrand on resources of indigenous plant species. Unpublished PhD Thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg.

|

Citation | | Williams, V.L., Raimondo, D., Dold, A.P., Crouch, N.R., Cunningham, A.B., Scott-Shaw, C.R., Lötter, M. & Ngwenya, A.M. 2008. Cryptocarya myrtifolia Stapf. National Assessment: Red List of South African Plants version 2024.1. Accessed on 2026/02/15 |

Comment on this assessment Comment on this assessment

|

© M. Lötter

Search for images of Cryptocarya myrtifolia on iNaturalist

|

Comment on this assessment

Comment on this assessment